The Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange might just be the most overlooked game-changer in world history. When Christopher Columbus and his crew stumbled upon the New World, they unknowingly kicked off a global remix of plants, animals, people, and—unfortunately—diseases that forever changed the planet. The results? Landscapes transformed, cuisines revolutionized, populations decimated, and yes, the ingredients for pizza were finally brought together (and no, we’re not saying pizza caused mass death—let’s keep that straight). Think we’re exaggerating? Buckle up and read on.

When Columbus veered about 6,000 miles off course and landed in the Caribbean instead of Asia, he wasn’t looking for tropical beaches or cultural exchanges. Nope, Columbus was laser-focused on gold and glory. Instead, he found the Arawaks—naked, friendly islanders offering shiny trinkets and feathers. Not exactly the golden jackpot he’d hoped for. But with some not-so-gentle “encouragement” (cue swords and steel), the Arawaks reluctantly pointed him toward gold. And that was all it took to infect Europe with gold fever. Within fifty years of Columbus’s arrival, 90% of the Arawaks had perished, mostly from smallpox, and two massive empires—the Aztecs and the Incas—had been toppled, reduced to colonies ruled by Spain.

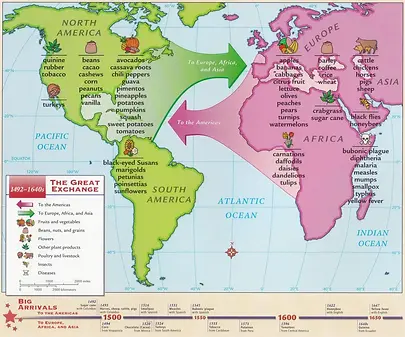

Imagine a world without chocolate, tomatoes, or French fries. Hard to picture, right? Before the Columbian Exchange, that was reality. When Christopher Columbus and other European explorers arrived in the Americas, they not only encountered new lands and cultures—they also kicked off one of the most important swaps in human history. This exchange wasn’t about trading gold or spices; it was about plants, animals, and ideas moving between the Old World (Europe, Africa, and Asia) and the New World (the Americas). The results reshaped life on every continent.

From the Old World came familiar animals like cows, pigs, horses, and sheep. These creatures weren’t just walking protein bars—they transformed how people farmed, traveled, and ate in the Americas. Horses, for example, revolutionized transportation for Native American groups on the Great Plains. Meanwhile, Old World crops like wheat, rice, and sugarcane changed the diets of people across the Americas. On the flip side, the New World introduced the Old World to foods like potatoes, corn, tomatoes, and cacao (yes, the stuff that makes chocolate). These crops became staples in European diets and fueled population growth across the globe. It’s no exaggeration to say that the Columbian Exchange changed the way people lived—and ate—forever.

Filthy Rich and Rotting Teeth

If you were a colonists with big dreams of becoming filthy rich forget about planting potatoes and instead put your money on those rare crops that Europeans couldn’t grow themselves. Exotic crops from Asia like sugar cane, rice, indigo (a plant used to make a blue dye) and coffee grew well in the warm subtropical climates of the Caribbean and Southern parts of America. Until 1800, when the cotton gin was invented, sugar was the king of the Caribbean. Every Caribbean island was converted into a huge sugar plantation populated by African slaves. It may come as a surprise that the sweet stuff is a grass that originated in the tropics of southern India, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea. Ancient Indians wrote recipes for drying sugar syrup into Khanda— which is where we get the word ‘candy’. The Chinese established the world’s first sugar plantation in the 600s.

In 1492, Columbus brought a cutting of sugar cane with him on his first voyage to the West Indies. But to Europeans, sugar was an expensive luxury reserved for making Christmas cookies. Housewives kept their sugar supply under lock and key. But in the 17th century, sugarcane was found to thrive in the tropics of the Caribbean and it wasn’t long before millions of slaves were being hauled off to the Americas and millions of pounds of crystallized sugar and rum (which is made from sugar cane) were being exported back to Europe. These plantations were producing 80-90% of the sugar consumed in Western Europe. By the 19th Century sugar cane plantations were booming and sugar had become something that everyone could afford. Children’s teeth would never be the same.

Cow's Milk, Disease, and the "Magic" of Conquest

When you look at the numbers, it seems impossible that a few thousand European colonists could conquer continents teeming with millions of Indigenous people. Historians estimate that, before European contact, the Americas were home to around 50 million people—although the exact number is still hotly debated. Outnumbered by ratios of 1,000 to 1 (or more), how did the Europeans succeed? The answer wasn’t their guns, ships, or even their cunning—it was something far smaller and deadlier: germs.

Within a few decades of contact, most Native American communities had been decimated, with some losing as much as 90% of their populations. Entire villages vanished, leaving behind ghost towns where thriving cultures had once lived. Take the story of the Pilgrims and the "friendly Indian" Squanto, who famously helped them plant corn and survive their first brutal winter. That alliance was real, but it may have looked very different if diseases introduced by European fishermen a decade earlier hadn’t already swept through the area. By the time the Mayflower landed in 1620, vast stretches of land were eerily empty, the once-thriving Wampanoag villages reduced to abandoned settlements.

This mysterious force wasn’t magic, as some Native Americans believed, but something even more insidious: disease. The concept of germs wouldn’t even be discovered until 1864, when French scientist Louis Pasteur put forward his groundbreaking germ theory. Until then, the devastation caused by smallpox, measles, and influenza remained an inexplicable horror to those affected. For Native Americans, these diseases spread with ruthless efficiency, as their immune systems had never encountered them before.

Europeans, meanwhile, carried these viruses in their bodies like ticking time bombs. They weren’t magical beings (despite some Indigenous beliefs that their immunity came from dark powers). The truth was far more mundane and, frankly, gross: centuries of close contact with domestic animals in Europe, Asia, and Africa had bred an immune resilience to many diseases. From cows, they got milk—and tuberculosis. From pigs and horses, they acquired influenza. Smallpox, a virus that originated in Africa over 3,000 years ago, had ravaged India, China, and Europe long before making its way to the Americas. While these diseases had been devastating for Eurasian populations in their time, survivors passed on genetic resistance to their descendants—a process that Native American communities never had the chance to experience.

Even long before Columbus, other cultures were already experimenting with ways to battle disease. Buddhist nuns in 10th-century China practiced "variolation," a rudimentary form of vaccination where healthy people were exposed to small amounts of disease to build immunity. It was a risky gamble, but over time, it worked. By the time Europeans arrived in the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries, their immune systems had centuries of practice fighting off these deadly diseases. Native Americans, by contrast, had no such advantage.

Why it Matters

By now, you’ve probably realized just how world-changing the Columbian Exchange was. When Europeans brought Old World crops, animals, and (unfortunately) diseases like smallpox and measles to the Americas, they didn’t just change the lives of Indigenous peoples—they rewrote the story of the planet. Species that had evolved separately for tens of thousands of years were suddenly sharing the same space. Imagine: the rattlesnake of the Americas meeting the viper of Eurasia, or wheat from Europe and corn from Mexico thriving side by side. It didn’t take long—just a few hundred years—for the Americas to start resembling a new version of the Old World. Today, when you picture endless fields of wheat or corn, you probably think of places like Iowa or Alberta, but their roots are part of this monumental exchange.

The Columbian Exchange sparked the greatest global trade network the world had ever seen. For the first time in history, people everywhere had access to cheap sugar, turkey dinners, potato salad, corn on the cob, hot cocoa, and Cuban cigars. This wasn’t just about food—it was about creating connections that would change cultures, economies, and diets forever.

Test Page