Motivations for Colonization

The Reasons Europeans Sailed Across the Ocean

Let’s be honest—moving across the ocean in the 1600s wasn’t a vacation. You didn’t hop on a ship for the legroom or gourmet meals. You were crammed into a wooden tub with rats, bad water, and seasickness as your daily reality. So why did tens of thousands of Europeans leave behind everything they knew and head for the unknown?

The answer depends on who you ask. Some were chasing wealth. Others were fleeing prisons. Some wanted to worship freely. And a few were just trying not to starve.

I's estimated that about 1.5 to 2 million people were brought to or migrated to North America between 1600 and 1750.

Land, Land, and More Land

In Europe, land was power—but most land was owned by wealthy nobles. But, In the New World, even poor settlers could get land (if they survived long enough). This was a big deal, especially for younger sons who weren’t set to inherit anything back home. Under England’s laws, the oldest son got everything. The others? Well, sorry about your bad luck.

So, colonists packed up and headed west across the Atlantic Ocean, hoping for space to build farms, raise families, and get out from under the heavy boots of European nobles and landlords.

Religion: Pray Your Own Way

Not everyone was chasing gold. Some were chasing God—or at least trying to escape people who didn’t like how they worshipped.

Take the Pilgrims, for example. These English Separatists believed the Church of England was too corrupt to fix. This kind of talk could get you imprisoned or worse. Therefore, in 1620, they decided to set sail for the New World. They didn’t end up where they planned, but they made it work. With help from the Wampanoag, they survived—and then built a society where their religious views ruled.

A few years later came the Puritans, who also wanted to “purify” the church—but not separate from it. They weren’t exactly big fans of religious tolerance. If you disagreed with them, you were likely to be fined, kicked out, or worse. Just ask Roger Williams, who got booted from Massachusetts for saying people should have freedom of religion. He founded Rhode Island, where people could finally worship as they pleased.

Down in Pennsylvania, William Penn welcomed Quakers and other religious minorities. Maryland started as a safe haven for Catholics. All across the colonies, religion wasn’t just a reason people came—it shaped how they built their communities.

Debt, Desperation, and Second Chances

If you were poor in 1600s Europe, your future was already decided—and it wasn’t looking good. There were no safety nets, no job programs, no second chances. But across the Atlantic? There was land, opportunity… and a dangerous deal waiting.

Enter the indentured servant. These were men, women, and even teenagers who couldn’t afford the cost of the voyage to America. So they signed contracts promising to work for 4 to 7 years in exchange for passage. Room and board were included. Freedom—if you survived—was the final reward.

It sounds simple, but life as an indentured servant was anything but. You could be worked from sunrise to sunset, clearing land, planting crops, hauling water, or doing backbreaking labor for someone else’s gain. Sick? Injured? Tough luck—your contract could be extended. Break the rules? You might be whipped, branded, or punished with more years of labor.

Not all indentured servants signed up willingly. Some were tricked or kidnapped, especially children. Others were convicts, orphans, or war prisoners shipped out by the English government to empty jails and reduce poverty. After the English crushed rebellions in Ireland and Scotland, they rounded up captured soldiers and sent them to the colonies in chains—not as slaves, but not exactly free either.

Between 1650 and 1750, historians estimate that over half of all immigrants to the thirteen colonies came as indentured servants. In places like Virginia and Maryland, they made up the majority of the labor force before slavery became widespread. The colonies didn’t just grow on dreams—they grew on contracts, hardship, and the hope that seven years of pain might lead to a better life.

For some, indentured servitude was a death sentence. Disease, abuse, and exhaustion killed many before they ever finished their contracts. But for those who made it through, freedom in the New World came with real possibilities: land, wages, and independence.

It’s important to note—this was not the same as slavery. Indentured servants had a contract and a way out. Enslaved Africans were forced into labor for life, with no rights, no freedom, and no promises. But both systems were built on exploitation—and both helped fuel the rise of colonial America.

During the peak immigration years (1620-1750) it's estimated that 50-67% of colonists who came to the Thirteen Colonies were indentured servants.

And Then There Were the People Who Didn’t Choose

Long before English ships arrived in Jamestown, Spain had already started bringing enslaved Africans to the Americas. As early as 1502, enslaved people were transported to Hispaniola to replace Native laborers who were dying in huge numbers due to disease, starvation, and overwork. By 1518, the Spanish crown officially authorized traders to import Africans directly from West Africa to the New World—launching what became one leg of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

The Spanish used enslaved Africans throughout their empire—from sugar plantations in the Caribbean to silver mines in South America. These early forced migrations laid the groundwork for a system of slavery that would expand across the Americas for centuries.

In the English colonies, the first recorded Africans arrived in 1619, brought to Virginia. At first, some may have worked as indentured servants, like poor Europeans, with a path to freedom. But by the late 1600s, colonial laws began to define slavery by race and heredity. Africans were enslaved for life, and their children were born into slavery.

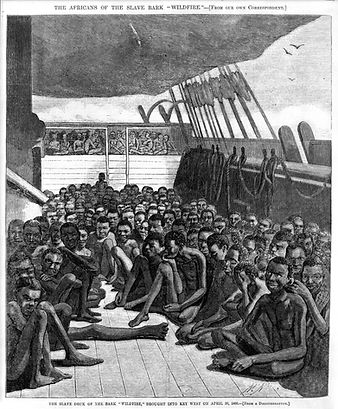

By the 1700s, chattel slavery—where people were treated as property—was deeply woven into the Southern economy. Crops like tobacco, rice, sugar, and indigo relied heavily on enslaved labor. Colonies grew rich, while millions of Africans were taken from their homes, shipped across the ocean in horrific conditions, and forced to work under brutal systems.

Still, enslaved people resisted in every way they could—through rebellion, escape, sabotage, and preserving their language, music, and traditions. Their stories are often left out, but they were vital to the history and economy of colonial America.

The Slave Deck of the Bark “Wildfire”

Why It Matters

The reasons Europeans came to America—land, wealth, religion, trade, and forced labor—shaped how the colonies developed. These motivations affected everything from where people settled to how they interacted with Native nations, how labor systems formed, and how governments were structured.

Colonies focused on trade or farming developed differently than those founded for religious freedom. Settlers who came for land expansion often pushed into Native territory, leading to repeated conflict. Economic goals like cash crop farming led to a growing demand for labor, which eventually fueled the expansion of slavery.

Understanding why people came helps explain why the colonies were so different from one another—and why patterns like land competition, forced migration, and unequal power structures continued for generations. These early decisions set the foundation for how the future United States would grow, govern, and deal with questions of freedom and control.

Test Page