Civil War Tech: How the War Became America’s First “Modern” Conflict

When we picture “modern warfare,” most people jump to World War II tanks or Vietnam helicopters. But the truth is, the first modern war happened much earlier—right here in America during the Civil War. Between 1861 and 1865, the battlefield became a brutal testing ground where 19th-century industrial power collided with old-school tactics. Generals trained to march men shoulder to shoulder suddenly had to reckon with weapons and machines that could kill at distances never seen before.

The Civil War was the moment where the United States learned that technology could change not just how battles were fought, but who won them.

Telegraphs: Lincoln’s Secret Weapon

By the 1860s, stringing telegraph wire was faster than laying down miles of couriers on horseback. Abraham Lincoln recognized its power immediately. He spent so much time in the War Department’s telegraph office that operators joked about him being their “night shift.” From there, Lincoln could send orders directly to generals in the field—something unheard of just a decade earlier.

One striking example came during the Battle of Chattanooga in 1863. Union reinforcements were rushed by rail from Virginia to Tennessee, and Lincoln kept tabs by telegraph the whole way. He called the combination of rail and wire “the modern miracle,” and for good reason: never before could an army move and communicate on such a scale. The Union’s ability to coordinate across hundreds of miles gave them an edge the Confederacy never matched.

Soldiers hustle wire from temporary pole to temporary pole. When the army moved, the communications system moved with it.

Railroads: Steel Arteries of War

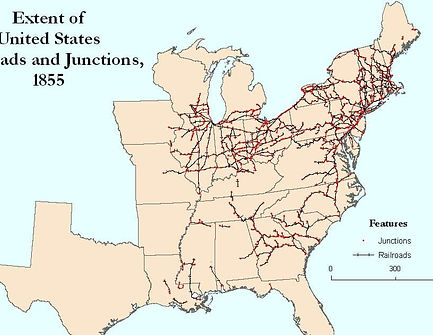

The Civil War was the first major conflict where logistics won battles as much as bullets. The North had over 20,000 miles of track compared to the South’s 9,000, and the Union system was far more standardized. Confederate trains often had to stop, unload supplies, and reload them onto cars of a different gauge—a logistical nightmare that slowed troop movements and wasted precious time.

The Union, by contrast, could send an entire corps by rail in a matter of days. In 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman’s march through Georgia was fueled by a steady stream of supplies coming down the tracks from Nashville. Soldiers joked that the railroad was their “iron lifeline.” Without it, Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea” would have been impossible.

States Rights: The Right to Do Your Own Thing

The South’s devotion to states’ rights and its agricultural economy meant railroads developed in fragments. Without standardized gauges or interstate cooperation, Confederate trains often had to unload and reload cargo at state lines—a costly weakness compared to the Union’s unified network.

Ironclads: The First Modern Battleship...Kinda?

Naval warfare changed almost overnight with the arrival of ironclads. The Confederacy, desperate to break the Union blockade, raised the burned-out hull of the old wooden USS Merrimack and rebuilt it as the CSS Virginia, a floating fortress covered in four inches of iron plating backed by thick oak. Its sloped sides deflected cannon fire, and when it steamed into Hampton Roads in March 1862, it smashed through the Union fleet, sinking the wooden USS Cumberland and setting the USS Congress ablaze in just hours.

For a moment, the Union blockade looked doomed.

But the North had been working on its own experimental warship, the USS Monitor. Unlike the Virginia, the Monitor barely stuck out above the waterline. Sailors joked it looked like a “cheese box on a raft,” with its revolutionary feature being a revolving gun turret that could fire in any direction. When the two ships met in battle on March 9, 1862, the clash was unlike anything the world had ever seen. For hours, cannonballs bounced off their armor harmlessly. Crowds on the shore expected one ship to sink in flames, but instead watched a slow, grinding stalemate. The battle ended without a clear winner, but it proved beyond question that wooden warships were obsolete.

Still, these early ironclads were far from perfect. The Virginia was slow and clumsy, struggling to make even five knots, and its outdated engines often broke down. The Monitor, while more agile, had serious flaws of its own—its low deck meant waves frequently washed over the ship, and poor ventilation left its crew gasping for air in combat. Neither vessel would last long; the Monitor sank in a storm off Cape Hatteras by the end of 1862. Yet their brief duel changed naval history forever. As one British observer put it, “The navies of the world must be rebuilt.” And they were.

USS Baron DeKalb in 1862

The scourge of Mobile - Confederate underwater mines, which back then were called torpedoes. This is a drawing in Harper's Weekly of the most common and deadly type - the Raines Keg Torpedo. A five gallon beer keg was sealed with pine pitch then filled with gunpowder and outfitted with a contact or electrical fuse. They could be anchored in place or attached to floats and allowed to drift on the tide towards anchored ships. The Confederacy deployed thousands of these, with the Mobile Bay area being especially concentrated. Though crude and prone to failure, they sank or damaged more Union ships during the war than enemy gunfire did.

Source: http://www.offthebeatenpath.ws/Battlefields/FortBlakeley/

Minié Balls and Rifles

When you think of modern warfare Vietnam or World War II probably pops into your head. If, on the other hand, you immediately think of Call of Duty, you might need to start cracking open those history books more often.

It might surprise you to know that the first modern war was the American Civil War. Officers on both sides were trained in outdated tactics using muskets and bayonets. But, the traditional tactics of stand in a line and shoot were going to get a whole lot of people killed in the first battles of the Civil War. The Battle of First Bull Run (July 21, 1861) taught everyone some hard lessons.

The minié ball, first developed by French manufacturer Claude-Étienne Minié, (pronounced min YAY but Americans say minnie) changed the battlefield forever. Before this time muskets rather than rifles were the weapon of choice for most modern armies. But the musket was slow to load and didn’t have a great accuracy beyond 100 yards. The minié ball was designed to be smaller than the barrel which made it faster to load. The four grease filled grooves made it spin increasing its speed and range. The new minié balls could accurately kill a man 500 yards away with such force that would tear through flesh and shatter bone.

The minié ball made the Civil War was the main reason for the high casualty rates on the battlefield. The Civil War also gained notoriety for the large number of soldiers who had to have their limbs amputated. This is because when the soft lead minié ball, no bigger than the width of your little finger, expanded and flattened out as it left the barrel. When it made contact it didn’t just break the bone it completely shattered it leaving army surgeons little choice but to amputate. The exact number is unknown but estimates put the number of amputees at around 60,000; or 10% of the total casualties.

Damaged femur bone from a minie ball shot

Clip from America Story of US

Balloons: The First Eyes in the Sky

Civil War generals didn’t have drones, but they did have balloons. The Union Army Balloon Corps, founded in 1861, sent observers aloft to sketch enemy positions and signal troop movements. At the Battle of Fair Oaks, a balloonist spotted Confederate reinforcements moving into position, allowing Union troops to brace for the attack.

It wasn’t foolproof—the balloons were slow, clumsy, and obvious targets—but the idea was revolutionary. For the first time, armies could see the battlefield from above, planting the seeds of modern military aviation.

The Union Army Balloon Intrepid being inflated from the gas generators for the Battle of Fair Oaks.

Mathew Brady

Medicine and the Ambulance Corps: Fighting to Save Lives

With new weapons came horrifying new wounds. Infection killed twice as many soldiers as bullets, largely because doctors had little understanding of germs. Still, advances emerged. The Union’s Ambulance Corps, organized in 1862, created the first system of trained stretcher bearers and wagon drivers to evacuate the wounded quickly. It sounds basic today, but it was revolutionary at the time.

Anesthesia, mostly chloroform and ether, was also widely used—disproving the myth that Civil War soldiers always “bit the bullet.” In fact, records show about 95% of surgeries were done with anesthesia. What they lacked was sterilization: surgeons often wiped bloody hands on their aprons before moving on to the next patient.

Detail from “Ambulance of the 6th Corps,” Matthew Brady. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Photography: War Hits Home

Photography was still a young invention when the Civil War began. The very first permanent photograph had only been taken in 1826 by Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, and daguerreotypes—shiny images on silvered copper plates—had only become widespread in the 1840s. By the 1860s, technology had advanced just enough that cameras could be carried into the field, though they were still bulky contraptions requiring tripods, glass plates, and chemical processing tents that smelled strongly of ether and smoke.

That’s what made Civil War photography so revolutionary. For the first time, war wasn’t just painted in heroic brushstrokes or sketched by newspaper artists—it could be captured exactly as it was. Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and Timothy O’Sullivan were among the best-known photographers who trailed armies with their equipment, setting up mobile darkrooms in wagons.

They couldn’t capture moving battles—exposures were too slow—but they could record the aftermath: fields strewn with bodies, destroyed homes, weary soldiers staring straight into the camera lens.

Brady shocked the nation in 1862 when he exhibited photos from Antietam in his New York studio. Visitors filed in expecting gallant portraits of Union heroes and instead saw bloated corpses on the battlefield. “The Dead of Antietam,” one newspaper wrote, had “brought home to us the terrible reality of war.” These weren’t distant casualties listed in the paper—they were human faces, and for many Americans, the first time they had seen war’s brutality unfiltered.

Reporters used the images as proof. Newspapers and magazines couldn’t yet print actual photographs in mass circulation, so engravers copied them into illustrations, spreading their impact further. Even so, the raw photographs circulated in galleries, shops, and private collections, leaving a permanent imprint on public memory. The Civil War became the first conflict where ordinary citizens could look directly at the cost of war—and once they had, the nation could never see war the same way again.

Private Bruce Shipman, 76th New York, Co. K. Courtesy of the U.S Army Heritage and Education Center

Image collection from: https://allthatsinteresting.com/civil-war-photos

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why It Matters

The Civil War was more than North vs. South—it was the moment war itself changed. Telegraphs gave leaders instant communication. Railroads carried armies like never before. Rifles and Minié balls turned traditional tactics into suicide missions. Ironclads rewrote naval strategy. Balloons offered a glimpse of the future in the skies. And photography brought the carnage home in ways words never could.

By 1865, the United States had fought not just a civil war, but the world’s first industrial war. The lessons were brutal, but they shaped every major conflict that followed.

Test Page