The Confederate States of America

Listen to the audio version.

Inside the Confederate Government

When Southern leaders stormed out of Congress in 1860, they weren’t just throwing a political tantrum. They believed the Union had drifted too far from their interests—and more importantly, from the protection of slavery. Within weeks, they began stitching together a brand-new country: the Confederate States of America. One, they believed, that would restore the “true” vision of the founding fathers. What they actually created was a government pulled in two directions at once—part U.S. Constitution, part Articles of Confederation, and fully unprepared for the industrial war it was about to fight.

Map of the Confederate and Union States in 1861.

Listen to the audio version.

The Confederate Constitution:

Familiar Shape, Very Different Goals

When the Southern states broke away, they didn’t have time to reinvent the wheel. So, they copied most of the U.S. Constitution and used it as the framework for their new government. Three branches. A president. A Congress. Courts. Checks and Balances. If you skimmed it quickly, you might think you were reading a slightly edited version of the original.

For starters, the Confederacy absolutely kept the rights Americans recognized from the Bill of Rights. Free speech, the right to bear arms, trial by jury, habeas corpus. But, those rights only applied to free people, and anything involving slavery was automatically outside their reach.

The biggest difference between the two constitutions was over slavery. The U.S. Constitution never said the word “slavery.” Instead, it danced around it. The Confederate Constitution did the opposite. It named slavery outright and put it front and center. Slaveholders’ rights were protected in every Confederate state and in any new territory the Confederacy might someday claim. Congress was forbidden from passing any law that threatened a slaveholder’s property rights. In effect, the Confederacy built a political system where slavery was not just legal but untouchable.

The presidency also got a makeover. Confederate leaders wanted stability without re-election battles, so they settled on a single six-year term. Jefferson Davis didn’t have to campaign, shake hands, or worry about political rivals gearing up for the next election cycle. The president also had a line-item veto, a tool that U.S. president still don’t have. Instead of being forced to accept or reject a whole bill, the Confederate president could cross out specific spending lines of a bill that they didn’t agree with. It was meant to stop waste and sneaking in special favors.

Where the Confederacy really broke from the U.S. system was in federal power. Southerners had spent decades complaining that Washington acted like a bossy neighbor who wouldn’t mind his own business. Now they had their chance to cut the national government down to size. The Confederate Constitution trimmed federal authority in trade, taxation, and national planning. States kept far more independence and could push back when they thought Richmond (the Confederate capitol) overstepped. And pushed back they did.

Article 1 Section 9 of the Confederate Constitution made it illegal to make slavery illegal.

The Confederate Constitution was ratified in Montgomery, Alabama until the new capitol was moved to Richmond, VA in May of 1861.

Listen to the audio version.

A Government Unprepared to Fight a Modern War

From the start, the Confederacy faced a financial uphill climb. The Southern economy was built on agriculture, not industry, and it relied heavily on exporting cotton to Europe. That meant the region didn’t have the factories, banks, or the large tax base the Union had. The U.S. government could raise money through tariffs, income taxes, and a strong network of northern industries that paid those taxes. The Confederacy couldn’t. Its wealth was tied up in land and enslaved people — neither of which produced steady federal revenue. In peacetime, this wasn’t obvious. In wartime, it immediately became a crisis.

The power to levy taxes was allowed but collecting them was another story. The Confederacy relied on state governments to assess and collect those taxes, and many treated the process like a suggestion. Some states delayed tax assessments, others undervalued property, and a few simply ignored federal tax laws altogether. Georgia’s governor, Joseph Brown, openly resisted anything that looked like federal power; he stalled tax collections, complained that Richmond was overreaching, and insisted Georgia’s resources belonged to Georgia first.

North Carolina’s governor, Zebulon Vance, took a similar approach, blocking federal agents and sparring with Jefferson Davis over what the national government could demand. With governors fighting the system from the top and local officials dragging their feet at the bottom, real revenue barely reached the treasury. In desperation the government began printing more money, and predictably inflation soared. Congress eventually resorted to taking ten percent of farmers’ crops because the cash system had collapsed.

As the conflict deepened, the cracks widened. The Confederate government struggled to coordinate basic wartime needs. Railroads refused to standardize track gauges or share equipment, making shipments slow and unreliable. Some state warehouses guarded their uniforms and boots for “their own men,” even as soldiers elsewhere marched with bare feet and torn jackets. Taxation was nearly impossible. Conscription sparked backlash from governors who insisted it violated state sovereignty. Every time Richmond tried to centralize anything, the states pushed back.

A political system built on resisting national authority couldn’t suddenly switch gears and run a unified war machine. The Confederacy kept discovering that what sounded noble in peacetime—local control, state independence, suspicion of federal power—became a disaster when armies needed food, rails, weapons, and men moved quickly and efficiently. The Union, with its stronger national structure, had the advantage the moment the war left the campfires and hit the supply depots.

Confederate States $100 bill

Each railroad company and state set their own standards for how wide (the gauge) the railroad tracks could be. This made it impossible for trains to cross state lines if the gauges were different. Instead the entire train would have to be unloaded and reloaded.

Source: Railroads.com

Listen to the audio version.

Leadership Problems

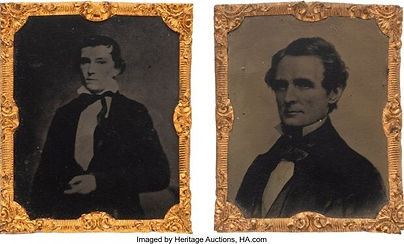

In addition to money problems, the Confederacy also had leadership problems. The Confederacy chose Jefferson Davis as president, hoping his military background and calm approach would hold everything together. But Davis’s personality made teamwork feel like pulling teeth. He was intense, proud, and famously thin-skinned. Once he settled on an idea, he locked onto it tighter than a terrier on a chew toy. He didn’t enjoy compromise, he didn’t enjoy being challenged, and he definitely didn’t enjoy governors treating his requests like junk mail. Jefferson’s attitude might work in an army, but he was a world leader now.

Vice President Alexander Stephens didn’t make things easier. Sharp and outspoken, Stephens supported secession but became one of Davis’s most frequent critics once the war began. The two men drifted so far apart that they sometimes went months barely speaking. At a time when the Confederacy needed its leaders on the same page, its highest offices were already running separate tracks.

Vice President Alexander Stephens (right)

President Jefferson Davis (left)

Listen to the audio version.

Why It Matters

Understanding the Confederacy as a government—not just a rebellion—explains why it collapsed long before the final surrender at Appomattox. Its leaders built a nation designed to protect slavery and preserve state independence, not to fight a coordinated, industrial war. The Confederacy mixed the familiar framework of the U.S. Constitution with the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation and then discovered too late that a government built to avoid central authority cannot survive a conflict that requires it.

Union victories mattered. But the Confederacy’s political structure helped defeat it from within. The leaders who claimed they were building a stronger, freer nation created a government that couldn’t enforce its own decisions or keep its states moving in the same direction. That contradiction—state independence vs. national survival—shaped the war just as much as any general or battle.

Digging Deeper

Use the article to answer the questions below.

-

Why did the Confederate States form their own government during the Civil War?

-

Name three key differences between the Confederate government and the United States government.

-

How did the Confederacy organize its military and war effort?

-

How did leadership problems weaken the Confederate government during the war?

-

How did taxes and funding shortages affect the Confederacy’s ability to fight the war?

Copy and paste the questions onto a Word or Google Doc

Examining the Confederate Government

Take your students inside the Confederate government with this structured Civil War Era Scratch Pad activity designed to move beyond memorizing facts. Students compare Union and Confederate systems, examine how state sovereignty shaped wartime decisions, and connect political structure to real battlefield consequences.

Test Page