Indian Removal & The Trail of Tears

Listen to the audio version.

The Land Grab: Why Did This Happen?

By the early 1800s, America was growing fast, and the push for new land was relentless. Settlers wanted the fertile lands in the southeastern United States, where Native American tribes had lived for centuries. The cotton boom only made things worse—everyone wanted to cash in on the “white gold.”

Then, in 1828, real gold was discovered in Georgia—right in the middle of Cherokee territory. Within just a few years, between 6,000 and 10,000 miners poured into the region between the Chestatee and Etowah Rivers, digging up Cherokee land and building mining camps across their farms and towns. The rush upended daily life, driving the Cherokee from fields they had tended for generations and bringing waves of outsiders who ignored tribal boundaries and laws.

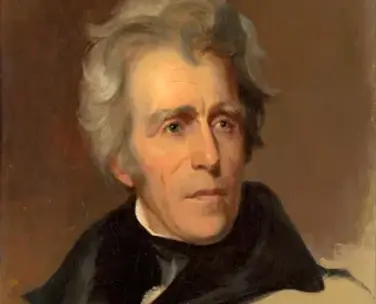

President Andrew Jackson, a man who considered himself a champion of the “common man,” led the charge to remove Native Americans from their land. To settlers, Jackson was a hero. To Native Americans, he was the man responsible for their suffering. His belief was simple: Native Americans and white settlers couldn’t coexist. He often said that removal was for the tribes' own good, but his actions told a different story.

Watercolor by Cookie Ballou

August 1, 1829 article from the Georgia Journal documenting the discovery of gold. From the Milledgeville Historic Newspaper Archive

Listen to the audio version.

The Cherokee and Assimilation: A Fight to Stay

After the American Revolution, leaders like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson insisted that Native nations could survive only by adopting “civilized” ways. They wanted Native people to farm, speak English, become Christian, and live like white settlers. While some tribes resisted, the Cherokee and their neighbors—the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—tried to adapt.

By the early 1800s, Cherokee towns looked different. Families fenced off farmland, grew corn and cotton, and built log cabins with chimneys. Men wore coats instead of hunting shirts, and women sewed dresses and bonnets. Wealthier families even owned enslaved Africans—an agonizing attempt to prove they could succeed in a world that measured worth by wealth.

Schools began appearing across Cherokee country. Children studied English and Cherokee side by side, and new laws and courts gave shape to a government built to defend their land.

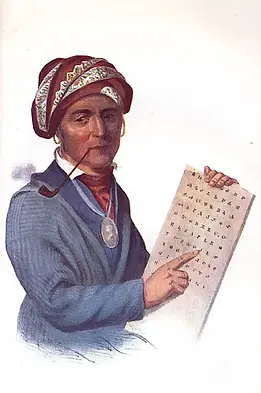

In 1821, Sequoyah created a written form of the Cherokee language. The Cherokee quickly put this written language to use. They published books, religious texts, and, most famously, a newspaper called The Cherokee Phoenix. Printed in both Cherokee and English, the newspaper became a powerful tool for uniting the Cherokee people and advocating for their rights. It also served as a platform to share news and warn of the growing pressure to give up their homeland.

In 1827, the Cherokee wrote a constitution declaring themselves a sovereign nation. But their success only fueled resentment. The more the Cherokee prospered, the more settlers wanted what they had.

Christianity and Missionaries

Christian missionaries spread throughout Cherokee territory, preaching conversion and education. Many Cherokee joined new churches, blending Christian teachings with their own traditions. Others remained loyal to older beliefs, but even the most traditional leaders saw value in learning how to navigate white society. Churches rose beside council houses and schools, symbols of a people trying to balance two worlds.

Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington, 1837-39, George Catlin

Listen to the audio version.

The Indian Removal Act and Andrew Jackson’s Role

In 1830, Jackson pushed Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act, which gave the federal government the power to “negotiate” treaties with Native tribes for their land. In reality, there wasn’t much negotiation—tribes were coerced, pressured, and even outright forced to sign treaties. Jackson justified the act by claiming it would “save” Native Americans from extinction by moving them to land where they wouldn’t be bothered. In truth, it was all about clearing the way for settlers.

Jackson’s attitude toward Native Americans wasn’t new. As a military leader, he had fought and defeated several tribes, including the Creek in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. He saw Native resistance as a threat to American expansion and believed removal was the only solution.

Andrew Jackson, 7th President, from 1829 to 1837

Listen to the audio version.

Why Assimilation Didn’t Work

For all their efforts, assimilation couldn’t save the Cherokee. Their success made them a target, not an equal. Settlers saw thriving Cherokee towns, well-ordered farms, and prosperous markets—and they wanted them. The more the Cherokee built, the more the U.S. government and Georgia lawmakers worked to tear it all down.

When Georgia began passing laws to strip away Cherokee rights and claim their land, the Cherokee turned to the courts. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation was sovereign and that Georgia had no authority over their territory. It should have been a victory. But President Andrew Jackson ignored the ruling, famously scoffing that Chief Justice John Marshall could try to enforce it himself.

The law was on the Cherokee’s side. Power was not.

Worcester v. Georgia (1832) began when missionary Samuel Worcester was arrested for living on Cherokee land without a state permit. Georgia claimed authority over Cherokee territory, but Worcester argued that only the federal government—not the states—could deal with Native nations. The Supreme Court agreed, ruling that the Cherokee Nation was sovereign. But President Andrew Jackson and Georgia ignored the decision, clearing the way for Cherokee removal and the Trail of Tears.

Listen to the audio version.

The Forced Eviction

The nightmare began even before the journey itself. Soldiers showed up at Native villages with little warning, ordering families to pack up and leave their homes immediately. Often, there was no time to gather belongings, and people were forced to abandon homes, tools, livestock, and heirlooms. Families were rounded up at gunpoint and herded into makeshift camps. These camps were overcrowded and poorly supplied, with little food or clean water.

Diseases like measles, dysentery, and whooping cough swept through these camps, killing many before the march even began. For those who survived, the conditions in the camps were only a grim preview of what lay ahead.

Trail of Tears 1839. Painting: “Forced Move” by Max Standley courtesy R. Michelson Galleries.

Listen to the audio version.

Conditions on the Trail

Once the march began, the suffering deepened. More than 60,000 people, representing all five native nations, set out for Indian Territory, but nearly 12,000 would never arrive.

Hunger struck first. The government promised rations, but supplies were late, spoiled, or stolen by corrupt contractors. Families dug for roots and stripped bark from trees just to stay alive. One soldier, Private John G. Burnett, later wrote, “The trail of the exiles was a trail of death… They had to sleep in the wagons and on the ground without fire… I have known as many as twenty-two of them to die in one night of pneumonia due to ill treatment, cold, and exposure.”

The weather made everything worse. The removal dragged on through blazing summers and into the brutal winter of 1838. Sleet and snow soaked thin clothes. Wagons froze to the ground, and coughing echoed through the camps. Reverend Daniel S. Butrick, who traveled with the Cherokee, wrote in his diary, “O what a year this has been! O what a sweeping wind has gone over, and carried its thousands to the grave; while thousands have been tortured and scarcely survive… For what crime then was this whole nation doomed to perpetual death?”

Again, disease traveled with them—dysentery, pneumonia, and fever spreading through every stop along the route. There were no doctors, no medicine, and nowhere to rest. Graves were dug into frozen ground, marked only by a stick or a scrap of cloth.

Still, the march continued. Families waited at frozen rivers for ferries that never came, standing in icy water until their legs gave out. Some died where they stood. By the time the survivors staggered into Indian Territory, they were thin, fevered, and hollow-eyed—alive, but only barely.

Listen to the audio version.

A Harsh New Home

The government called their new land “permanent Indian Territory.” The promise was that no state laws would ever reach them again. But the territory was a harsh, unfamiliar land. The soil cracked in the summer heat. Winter winds swept unbroken across the plains. Water was scarce. Tools and livestock promised by the U.S. rarely arrived, and when they did, they were often useless.

Disease followed the Cherokee west. Cholera and malaria spread through the settlements. Many who had survived the trail died within their first year in the new land. Still, the Cherokee began to rebuild. They planted corn, built houses and churches, and reopened The Cherokee Phoenix. In 1839, they established a new capital at Tahlequah and ratified a new constitution.

The Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole did the same, creating towns and governments throughout the territory. They started over, determined to hold on to what they had left.

But the promise of a permanent homeland would not survive the next century.

Native land in "Indian Territory" in 1830.

Listen to the audio version.

The Broken Promise of Oklahoma

By the 1850s, white settlers were sneaking into Indian Territory, building trading posts and farms. Railroads followed, cutting across land that had been guaranteed to the tribes. During the Civil War, the U.S. seized more territory for military use.

Then came the Oklahoma Land Runs. In 1889, the federal government declared millions of acres of “unassigned lands” open for settlement. Tens of thousands of settlers lined up on horseback and raced across the plains to claim land that treaties had promised to Native nations.

In 1907, the territory was dissolved entirely. The “Indian Territory forever” became the state of Oklahoma.

Native land in Oklahoma in 2025

Listen to the audio version.

Why It Matters

The Trail of Tears reveals lasting patterns in U.S. history—how expansion often came at the expense of those already living on the land, and how law and power rarely protected the powerless. It shows the limits of assimilation and the failure of the courts to shield Native nations from political pressure. The Cherokee story also set a precedent: even legal victories meant little without enforcement.

Test Page