The Oregon Trail: America’s Great Gamble

Listen to the audio version.

By the 1840s, life in the United States felt like a pot boiling over. The country was bursting with energy, ambition, and—let’s be honest—a fair amount of desperation. Economic depressions had crushed farms and banks. Land prices in the East had shot up, and wages were sinking faster than a wagon in prairie mud. So when stories spread about rich farmland in the Oregon Country—a place where the soil was dark, the rain actually showed up, and land was free for the taking—it lit up people’s imaginations like a gold strike.

Families sold everything they owned, packed up their wagons, and set off chasing what some called “Manifest Destiny”—the belief that America was meant to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific. But destiny didn’t come cheap. It came with blisters, broken wagons, and a whole lot of grit.

Listen to the audio version.

The Jumping-Off Points

If you wanted to head west, Missouri was your launch pad. Towns like Independence, St. Joseph, and Council Bluffs were called “jumping-off points” because that’s exactly what they were—the edge of civilization.

These towns exploded with business as merchants sold everything a pioneer could possibly need: flour, bacon, rifles, wagons, harnesses, oxen, tools, and the all-important coffee. One emigrant guidebook, written by Lansford Hastings, gave clear advice:

“In procuring supplies for this journey, the emigrant should provide himself with at least 200 pounds of flour, 150 pounds of bacon; ten pounds of coffee; twenty pounds of sugar; and ten pounds of salt.”

A family needed about 1,000 pounds of food to survive the six-month trek. A decent wagon cost around $100–$150, and each ox—your most valuable asset—was another $25. When you hit the trail, you weren’t just starting a trip—you were betting your future on wood, iron, and animal muscle.

Jumping Off Day in Fort Kearney, Nebraska

Listen to the audio version.

Why They Left

The people who hit the trail west weren’t thrill seekers—they were survivors. Many were farmers ruined by the Panic of 1837, when banks collapsed and crops sold for less than it cost to grow them. Others were craftsmen, teachers, or small shopkeepers searching for a new start.

Letters and newspapers painted Oregon’s Willamette Valley as a paradise. “Wheat grows taller than a man’s head,” one guide bragged. When the U.S. government passed the Donation Land Act of 1850, it offered 320 acres to every white male—or 640 acres for married couples—if they stayed and farmed the land for four years. The promise of free land pulled thousands of settlers west.

That promise, however, excluded many people. Oregon’s early laws barred African Americans from settling in the territory, and its state constitution in 1857 carried that restriction for decades.

The clause was not officially removed until 1926, long after white settlers had claimed most of the region’s farmland.

Despite these limits, the idea of starting over captured the national imagination. Families packed everything they owned into wagons and began the long journey west—hoping to find better soil, better weather, and a better life in Oregon’s valleys.

Listen to the audio version.

The Long Road West

The Oregon Trail stretched roughly 2,000 miles from Missouri to the lush valleys of Oregon. It took four to six months to cross—on foot, mostly. Only the sick, the elderly, or the very young got to ride in the wagons, which jolted and rattled like washing machines on rocks.

The ideal departure time was April or May, after the grass was high enough for grazing but before snow blocked the mountain passes. Leave too early, and your oxen starved. Leave too late, and you risked freezing to death in the Rockies.

Families didn’t go alone. They formed wagon trains—mobile communities of dozens of families who shared food, chores, and protection. At night, they circled their wagons for shelter and safety, though more from weather and wild animals than from attack.

Source Jim Dawes Oregon Trail Adventure

Listen to the audio version.

Life on the Trail

Once the wagons rolled out of Missouri, the trail became both home and routine. Every sunrise meant packing up camp, hitching oxen, and walking—mile after dusty mile. On a good day, wagon trains might cover 10 to 15 miles before making camp again at sunset.

Everyone worked. Men drove wagons and fixed broken parts. Women cooked over open fires, washed clothes in muddy streams, and tended to the sick or exhausted. Children gathered buffalo chips—dried dung used for fuel—and helped herd the animals. There was no such thing as a lazy day.

Meals were simple: biscuits, salted bacon, and coffee that could double as axle grease. At night, fires flickered under endless stars, and a little singing might drown out the sore feet and homesickness.

One traveler, Martha Morrison Minto, later remembered:

“It strikes me as I think of it now … the mothers on the road had to undergo more trial and suffering than anybody else. The men had a great deal of anxiety … but still, the mothers had the families.”

Another emigrant, Lavinia Porter, confessed the emotional toll:

“I would make a brave effort to be cheerful and patient until the camp work was done. Then … I would throw myself down on the unfriendly desert and give way like a child to sobs and tears, wishing myself back home.”

Women often worked long after the men were done for the day. As one pioneer woman complained, “We have no time for sociability… there is no rest in such a journey.”

Life on the trail wasn’t glamorous—it was grit, teamwork, and quiet endurance.

The rich farmland of the Wilmette Valley, located near Portland Oregon, was the main destination for pioneers heading west along the Oregon Trail

For safety, families often traveled in massive wagon trains.

Kids on the trail used to play with Frisbees made of buffalo dung!

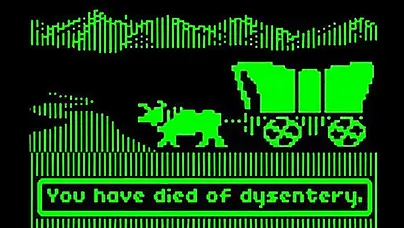

The Untold Truth About The Oregon Trail

Listen to the audio version.

Hardships , Hazards, and Honey Badgers

If routine defined their days, danger always lurked close by. And no, those dangers weren’t honey badgers. We just made that up to see if you were still paying attention. But the Oregon Trail has plenty of other things that could kill you, like snakes, disease, starvation, and exhaustion. The Oregon Trail was less an adventure and more a survival test.

Accidents were the biggest killers. Wagons crushed careless walkers, oxen bolted, and river crossings turned deadly in seconds. The unpredictable weather made things worse—tornadoes, hailstorms, flash floods, and scorching heat all claimed lives.

But the deadliest enemy was invisible: cholera. Spread by contaminated water, it struck without warning. A person could go from healthy to dead in less than a day. Historians estimate that about one in ten pioneers—roughly 20,000 people—died on the trail, most from disease.

A broken wagon axle could strand a family hundreds of miles from help. Smart pioneers carried spare parts and knew how to fix them. Those who didn’t often had to abandon their wagons and continue on foot, leaving their dreams scattered in the dust.

Despite all of it—the pain, exhaustion, and loss—most pushed forward. Turning back wasn’t an option.

Walk 2,000 miles to Oregon, they said! It'll be an adventure, they said! Pffft!

Listen to the audio version.

Reaching Oregon

After months of hardship, the sight of the Columbia River was a kind of miracle. But even that wasn’t the end. Some pioneers still had to raft their wagons down treacherous waters or climb through the Cascade Mountains before reaching the Willamette Valley.

When they finally arrived, the land lived up to its legend—green, fertile, and open. It wasn’t easy, but it was theirs.

By 1860, more than 400,000 Americans had traveled the Oregon Trail. Their journey transformed the map, reshaped the economy, and helped cement America’s expansion westward.

Listen to the audio version.

Why It Matters

The Oregon Trail shaped more than the map of the United States—it shaped the country’s character. It revealed how far people were willing to go for the chance to start over, and how that determination could build entire communities from little more than hope and hard work.

The trail showed what ordinary families could endure. They faced hunger, storms, and months of exhaustion but still pressed forward, driven by faith in a better life. Their journey helped populate the Pacific Northwest, expanded trade, and opened paths that later became railroads and towns.

The Oregon Trail also left lasting lessons about the cost of expansion. It brought opportunity for some, but displacement and exclusion for others. The ruts carved into the prairie remain as reminders of ambition, resilience, and the complicated legacy of a nation always moving forward.

CSI: Oregon Trail

A wagon found. Bones uncovered. A family lost to time. In CSI Oregon Trail, your students step into the role of forensic historians to solve a mystery from the Oregon Trail. Using diary entries, excavation data, and realistic lab reports, they’ll uncover what really happened to the Halbrook family in 1835.

Test Page